Writing the New Native Narrative

Madeline Easley (Wyandotte Nation) is a New York City-based actor and a 2021 Cultural Capital fellow. Originally from Kansas City, Kansas, she is a recent graduate of the University of Evansville where she received her Bachelor of Performance with a Minor in Creative Writing. Easely is a member of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma and seeks to incorporate her peoples’ stories into her artistic mediums. In performance, she is known for her comedic timing and for bringing classical qualities to modern work. In writing, Maddie focuses on telling Native stories rooted in her tribe’s traditions.

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to act and write?

I come from a family of storytellers. We're Native. We're always telling crazy stories and making each other laugh. My brother was into musical theater. I would see him perform and I was like, “Oh, I want to do that.” But come to find out, I cannot sing or dance. But I could act.

In my family, we had a rule about [attending] college outside of Kansas, where I was born. I had to get a scholarship. I tried everything. I played every sport, and I was the worst of the best. I was in the top tier [of athletes], but I was the worst one. I was offered scholarships [to attend college] and my tribe [provided] a housing stipend. All the pieces just fell into place. I majored in theatre at the University of Evansville, a liberal arts school in Indiana. And it was great. I loved it. I was the only Native person there.

On the other hand, I couldn’t tell my story. No one produced Native plays. There were no Native people to collaborate with. And so, I started writing. I picked a minor in creative writing and I wrote a one-woman show called Poolside Murder Party.

[During] my senior year, I started following a bunch of Native theater people. I connected with playwright and theatre director Tara Moses (Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Muskogee/Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Oklahoma), who is also a 2015 Artist in Business Leadership fellow. I just reached out and I was like, “Hey, I think you're spectacular.” She asked if I wanted to audition for her show. And I was cast in The True Story of Pocahontas.

Ever since then, I've been steeped in Native theater and film.

I want to learn more about your one-woman show Poolside Murder Party. What inspired you to tell that story? And what type of impact did you make?

My one-woman show was based on a short story that I had written about the Violence Against Women Act expiring in 2018. And the impact was that it was the first piece of Native theater that people [I knew] had seen. It was the first time I talked in depth about what it meant to be Wyandotte. [Audiences] were shocked that this was inside of me the whole time. People didn't know how to talk to me about [the subject].

I would ask, “What did you think of the performance?” It made people uncomfortable, which is natural. My show came from a desire to put my skills together [and to] base it on something that was close to me.

Is audience discomfort your overall objective as an artist? Or do you want audiences to learn new things?

My writing is fantastical realism, like borderline horror. It’s a mix of Midsommar (2019) by the entertainment company A24, the film Get Out (2017), and the classic novel Anna Karenina (1878). I want [Native audiences] to watch my work and feel like another facet of their experience is being explored. My [own] experience is very specific and it's not going to represent every Native person. I hope they understand something more about themselves. (Read Easley’s article The Only Thing ‘The Politician’ Needs to Cancel is Redface, published by Medium).

It sounds like your storytelling is focused on nurturing Native folks.

Yeah. I think the line that I will never cross as an artist is I won't [create anything] that would traumatize Native people. I'm not going to throw something up that has no purpose. I feel like horror rests on the Indian graveyard or a Native [character] who wakes up and is surrounded by dead tribal members.

What wisdom can you offer to emerging talent who want to go into performing arts?

Ground yourself in community. As Native artists, we don't operate the same way like non-Native artists. We're not only accountable to ourselves, but we have a whole community behind us and we're accountable to our tribes. Native people suffer from hyper-invisibility. Everything that we put out influences the larger story of who we are as a people and how we're treated.

What’s your next project?

I finished my first full-length screenplay called When We Lived There, which takes the Indian graveyard horror trope and reclaims it. The story is about a cult wanting to give land back to my tribe but then a horror story ensues. It’s going to be workshopped next week for the first time.

How has First Peoples Fund supported your art?

First Peoples Fund is investing in me as an early-career artist. I've never written a screenplay before, but they've decided I can do it and that they're going to support me in doing that.

“First Peoples Fund is like, ‘Oh, we believe in you. You just go do it.’ And I think that's amazing.”

***

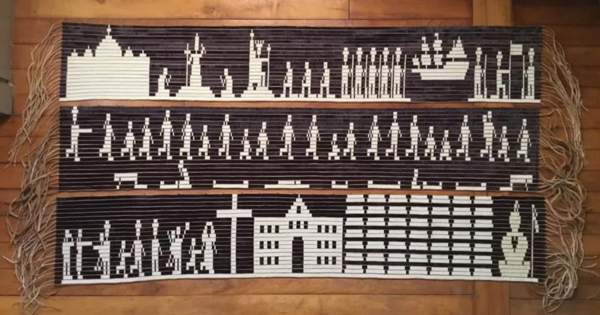

Madeline Easley is one of six Native women filmmakers who are debuting short films at We the Peoples Before, a celebration of Native culture, sovereignty, history, and vitality, produced by First Peoples Fund in February 2022 at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Click here to learn more about the screening and panel discussion.

Learn more about Madeline Easley on her website, Facebook, and Instagram.