Art Without Borders: Fostering Collective Spirit Among Global Indigenous Communities

“Kyrgyzstan is a breathtakingly beautiful country with landscapes that seem to rise from every horizon, where mountains cover 90% of the land. The view changes from deserts to pasturelands for miles, yet the mountains remain a constant, timeless presence. Here, Kyrgyz people continue to live in close relationships with their lands, honoring traditions that have been part of their lives for centuries. This enduring connection is felt in every aspect of life—in the nomadic yurt homes that dot the open landscapes, in the sight of herders wrangling hundreds of horses along ancient paths of the Silk Road, and in the foods lovingly prepared and served to us, echoing the warmth of meals shared in our Native communities back home.

Being in Kyrgyzstan, I was moved by the deep closeness to the land, language, culture, and creativity that shapes the lives of the Kyrgyz people. I felt a powerful sense of kinship—a recognition of family across miles and borders. I am profoundly grateful for the chance to witness this connection firsthand.” - Heidi K. Brandow

In the fall of 2024, several Native artists from the United States were invited to participate in an immersive Nomadic Art Camp experience in Kyrgyzstan. Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk), Clementine Bordeaux (Sicangu Lakota), and me, Heidi K. Brandow (Diné, Kanaka Maoli - FPF ABL ‘18). Made possible by Shaarbek Amankul (Kyrgyz-Zhediger), a visionary artist and the founder and director of the program, we traveled to a camp. We were joined by Central Asian curators, including Aygul Khaydarova from the Abylkhan Kasteyev State Museum of Arts in Kazakhstan, Muzaffara Ishanova from the State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan, and Nuttaphol Sinthavatorn representing the Museum of Contemporary Native Art (MoCNA). Since 2011, Amankul, a multidisciplinary artist, has led this project to connect artists from across the globe with Central Asia's art, culture, and landscapes. The critical ingredient is the traditional nomadic way of life as a source of inspiration for conceptual, contemporary and globally relevant art practice.

“My primary hope for this collaboration was to cultivate a space for genuine dialogue that transcends geographical and cultural boundaries,” says Amankul. “I envisioned an environment where artists from both backgrounds could share their narratives and experiences of navigating colonial legacies, ultimately promoting mutual understanding and respect.”

This drive to collaborate is deeply connected to Kyrgyzstan’s history as a former Soviet colony. In the post-Soviet era, the Kyrgyz people have been rebuilding and reaffirming their identity, which includes a renewed dedication to the Kyrgyz language, cultural practices, and relationship to the land—each an anchor for national identity.

As Native people, we can relate to this experience, as we, too, have endured generations of often violent subjugation by colonial and U.S. powers. This legacy continues to shape our communities today. We find common ground through these shared experiences and resilient journeys, fostering a unique space for understanding, healing, and solidarity. “My journey into creating a cultural exchange between Native American and Kyrgyz communities is deeply rooted in my personal experiences with identity and heritage.” Amankul continues, “By integrating artistic collaboration with community involvement, I aim to weave a rich tapestry of cultural exchange that honors artistic expression and our communities' lived experiences.”

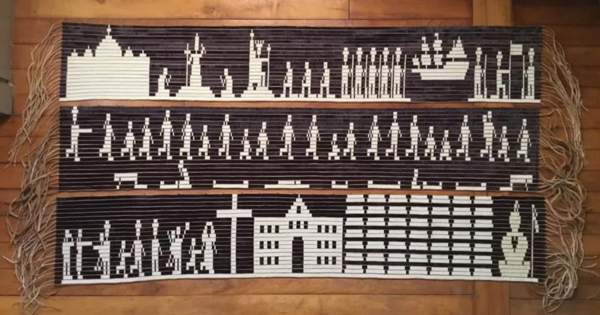

During our 12-day journey, fellow artist Clementine Bordeaux reflected on how her experience as a Nomadic Art Camp resident echoed her life in her Lakota community, where art and creative practice are woven into daily life. Coming from a rural background, Bordeaux is a champion of everyday artists, sharing her admiration for those who don’t necessarily see themselves as artists yet create beauty in their ordinary lives. She said, “The people who don’t consider themselves artists are often the ones I’m most eager to engage with—the everyday creators whose hands craft beauty in the ordinary. Whether it’s the student learning to draw, the art woven into a yurt, or the everyday material culture we wear, creativity thrives far beyond gallery walls. These simple, powerful acts of making are as much art as anything on display.”

Our artist group also found creative parallels between our cultural materials and the art of the Kyrgyz people. Artist Tom Jones shared, “Seeing the floral designs on the yurts immediately reminded me of home. The Ho-Chunk use similar applique patterns on our clothing—designs that reflect our deep respect for the earth and plants gifted to us by the creator.” This moment of recognition highlighted how cultural exchange drew us, as Native artists, closer to Central Asia's Indigenous people and traditions. These shared symbols of respect for the land and its gifts were powerful reminders of the common threads in our histories and practices, bridging our communities across continents.

Now more than ever, we as Native people need each other—and we need to embrace our kinship from a global Indigenous perspective. The Nomadic Art Camp, much like the First Peoples Fund’s Oglala Lakota Artspace on the Pine Ridge Reservation and our friends at Racing Magpie in Rapid City, South Dakota, exemplifies the importance of Indigenous artist-led initiatives, spaces that connect us and foster meaningful dialogue, creating pathways for long-term support in our shared efforts to decenter the West and reclaim our authority over our languages, cultures, and lands.

Why does this matter to First Peoples Fund? Why should it matter to you? Because in a world made smaller every day by technology—through social media, email, the internet, and travel—we are more connected than ever. It matters because, as we face mounting challenges, we must know that we’re not alone. We have the power to establish our metrics of success that are informed by generations of traditional Indigenous knowledge systems that meet our community’s needs. In standing together, we strengthen our path forward, ensuring that we—and the generations to come—are equipped to navigate whatever lies ahead, grounded in the strength of our shared identity and purpose.

Looking to the future of Nomadic Art Camp, Amankul shares, “Building relationships of solidarity among Indigenous peoples globally requires a deep commitment to authentic connection and openness.” He adds, “Cultural exchanges, exhibitions, collaborative artistic projects, and shared platforms for dialogue are essential for nurturing these bonds and fostering our collective spirit.”

Amankul has already begun discussions with museums and cultural institutions in Central Asia and the United States to create an exhibition showcasing art inspired by the Nomadic Art Camp experience. He also envisions this project expanding into educational settings, sharing, “Education plays a vital role in amplifying Indigenous voices and raising awareness about the ongoing impacts of colonization. By bringing our histories and perspectives into educational frameworks and public discourse, we foster a deeper appreciation for our struggles and celebrate the beauty of our cultures.”

Through these efforts, Amankul is creating lasting spaces for connection, collaboration, and learning—where Indigenous voices can resonate across borders, deepening our understanding of our shared journeys. To support the ongoing work of Nomadic Art Camp, consider donating to their GoFundMe campaign and following their journey on Instagram.

Additionally, two episodes of the Collective Spirit Podcast provide further context as a companion to this article: Episode 4 features Clementine Bordeaux, and Episode 5 presents a conversation with Shaarbek Amankul, Heidi K. Brandow, and Clementine Bordeaux. We hope you’ll listen, share, and follow this podcast series.