Final three 2013 Community Spirit Award ceremonies held in Alaska, Maine and North Dakota

There was no better way for First Peoples Fund to honor Susan Malutin than to take the time to travel to the very place where she is having such an impact.

Malutin was honored recently in a Jennifer Easton Community Spirit Award ceremony at the Native Village of Afognak's Dig Afognak Camp Site in Alaska.

"They had to fly to Kodiak Island and then take a skiff across the bay into the Afognak camp," said Malutin. "It made me feel so good that they would put that effort in to come all that way."

Malutin was not the only award recipient to experience an honoring ceremony close to home.

Community Spirit Award ceremonies were also held in North Dakota, in honor of Georgianna Houle, and in Maine, in honor of Watie Akins, over the past two months. They joined fellow honorees Denise Lajimodiere, Cyril Lani Pahinui, Vicky Takamine, who were honored in Hawaii this summer.

The awards are given to recognize the exceptional passion, wisdom and purpose the recipients bring to their art and the communities they serve.

"The resolve and determination shown by each of the individuals to pass down Native traditions touches us in ways that are often difficult to express," said Lori Pourier, president. "It was a joy to meet each of these recipients personally and to be among them in their communities."

Akins, a member of the Abenaki in the Northeast, has focused much of his life's recent work on restoring and passing along the Penobscot Nation's traditional songs through research, recordings, apprenticeship programs and work with local school students. Some of his family was able to attend the ceremony, which at times brought tears to his eyes.

"I thought the whole ceremony was good, every part was a touching experience."

The star quilt blanket, which is given to each CSA honoree, was a special gift, Akins said. He hopes that the attendees of the ceremony—particularly young people in his community—were inspired by the energy and resources available to them to move forward with cultural revitalization.

"I hope they get into it," he said.

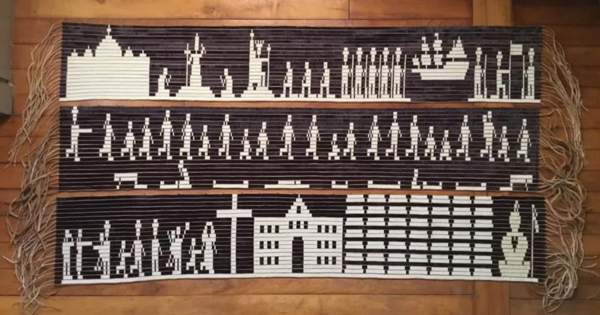

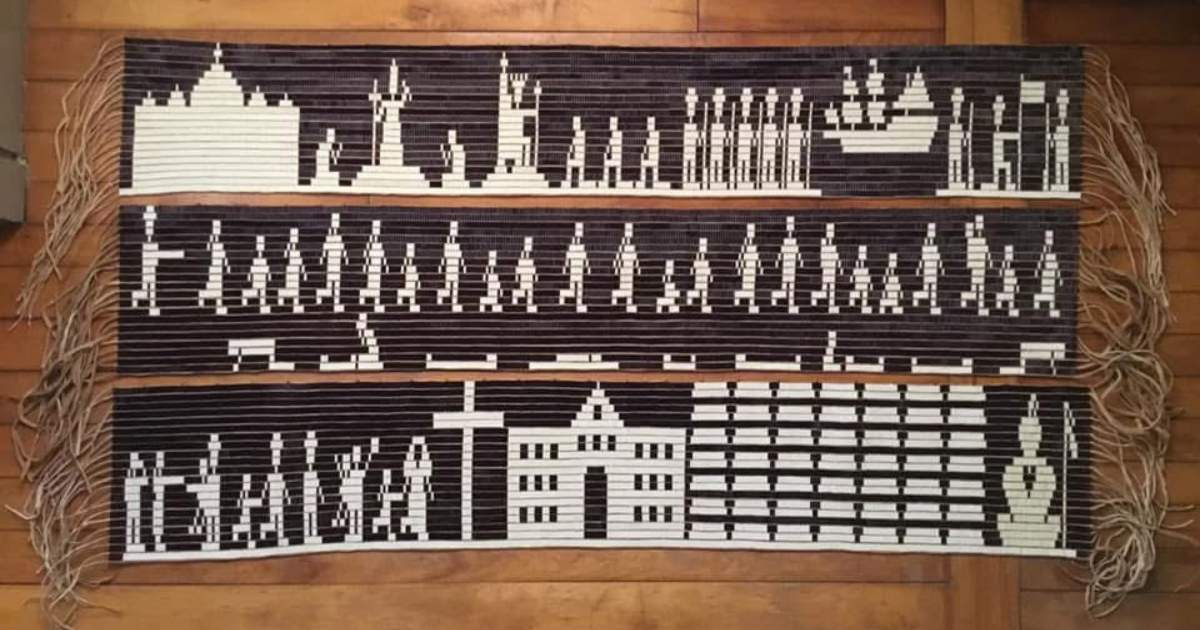

The ceremony to honor Georgianna Houle was held in her hometown of Belcourt, North Dakota. Houle, who is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, first learned to weave red willow baskets at the age of nine while watching her mother and grandmother. She has spent several years visiting local schools and community colleges, teaching children and adults how to weave the baskets.

She hopes to continue teaching and selling the baskets and is one of several artists who will teach at the Turtle Mountain Tribal Arts Association's new location in Belcourt.

Malutin, who has spent the last 30 years mastering the lost art of traditional skin sewing, has been credited with helping revitalize the Native culture and art of the Alutiiq people—a movement that that has rejuvenated elders and prompted the building of a Native museum.

She has traveled to countries all over the world to research Native pieces of clothing and artifacts from the island and spends time working with village schools to teach skin sewing and other Native traditions. She also spends time at the Afognak site several times a year to help teach at Native educational camps.

The honoring ceremony for her was intimate and beautiful, Malutin said.

"The whole camp was there and it was an amazing experience," she said.

Because the ceremony was at the camp, and not in town, the students were able to attend and felt comfortable to speak.

"These are normally shy kids," Malutin said. "But you become like a family here, and they were brave enough to talk about how I interacted in their lives. That was the greatest reward for me."

Malutin also felt a validation for her work, and a resurgence of energy to continue.

"I felt that yes, I am leaving my footprint in the culture," she said.

Uncertainty and self-doubt about whether she was teaching the traditions correctly, or instructing the students in a way that would encourage and challenge them, have always been in the back of her mind, she said.

"We have so few elders who remember how to do the parkas or how to sew skins," she said, and it was always her fear that she wasn't demonstrating it correctly, or making a difference in the lives of the people in her community.

The ceremony changed that, she said, especially after hearing from the students.

"It was such a family-oriented ceremony and I could see that we do have a really vibrant Native community here, and we are passing it down to the next generations."