2015 Community Spirit Award honoree working to leave a legacy for his tribe

There was no way to know that David Boxley Jr.'s (Tsimshian) first drawing lessons with his father at the age of four would turn in to a lifetime of artistry and achievement. But it was those early lessons, Boxley said, that helped teach him not only the mechanics of drawing—and later carving—at the age of six, but a respect for his Native culture and traditions.

Boxley, who has been named one of the 2015 Jennifer Easton Community Spirit Award honorees, will be honored in his hometown of Metlakatla, Alaska, later this year. Boxley is Tsimshian from the Metlakatla Indian Community.

Boxley's father, David A. Boxley, was also named a Community Spirit Award recipient in 2012.

"I have very big shoes to fill. It's lovely to be selected for something like this. First Peoples Fund is choosing to acknowledge people who make things better for their people and communities, and they deserve a big thanks for that."

Boxley said his father was a respected artist and culture bearer in their Alaskan community, adding that one of the strengths of his youth was witnessing a resurgence of their culture because of people like him. "I got to watch our culture come back," he said.

Their story is a perfect example of the strength and wisdom that can be passed from generation to generation, said First Peoples Fund President Lori Pourier.

"The Boxley family has demonstrated just what can happen when we are purposeful about teaching our kids not only the hands-on traditions and ceremonies of our people, but also the strength, integrity and drive that enables our culture to remain intact and thrive to this day," Pourier said. "We are thrilled to honor David this year, and celebrate the legacy this family has built."

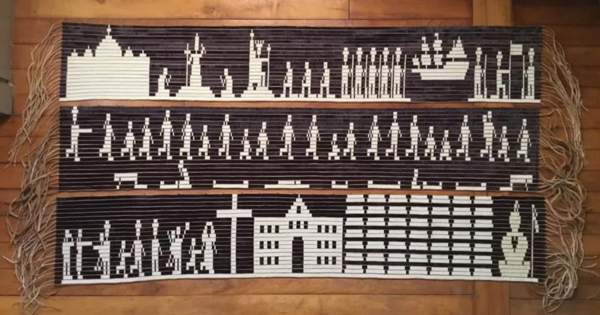

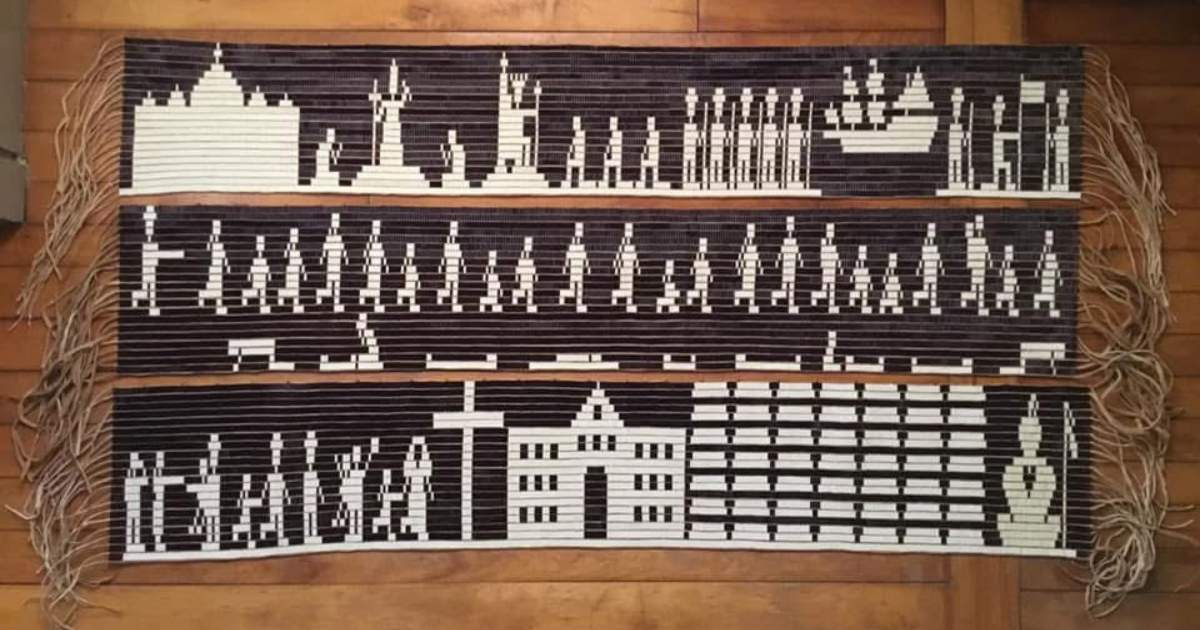

Boxley, whose art includes totem pole carvings, paintings, rattles and masks, said it's impossible for him to separate his work as an artist with the Native traditions. "I disagree with Native artists who only do the art and not the ceremonies," he said. "I don't see how that's possible. You can't have one without the other."

Boxley had originally planned to be an illustrator, first completing an apprenticeship in high school with an illustrator and later attending college to study more.

"But then I realized that most of the field is now digital," he said, "and that doesn't do it for me."

He returned to an old love—carving—and has since made it his life's work to revive his tribe's dying language, pass on the art to the younger generation, and perpetuate their traditions.

"I am what I do and I do what I am," Boxley said. "It's not a nine-to-five job, and even when I'm off, I'm still thinking about aspects of it. Whether it's the art or a language class or a piece, my thoughts are with my art and culture all the time."

Boxley said he experiences the most fulfillment when doing his tribe's ceremonies. "At the end of the day, when we're doing the ceremonies is when it's truly fulfilling and that's the real thing. That's why the art is made."

Boxley has no plans of slowing down this year. He is currently part of a group that plans to organize potlatches, or gatherings, to establish their village's old-style tribal name. Tribal names used to signify the land of where a group of people came from.

"One step back to reclaiming our heritage is to have a proper name on the tribe or village," he said.

In August, people will gather to hear information from Boxley and others about why they should rename the village. A totem pole will then be raised in 2017 and the new name will become official.

Boxley is also at the center of an effort to revitalize his tribe's language. He will join a group of people who will study and become fluent in the language, part of an effort to create fluent speakers who can then lead immersion schools. "We can hopefully extend the life of the language another 50 years," he said. "I know I will have to sacrifice art time, but there's nothing more important."

Language is the distinguishing factor for tribes, he said.

"One thing that makes my people unique is our language," he said. "All of the tribes on the Northwest Coast have totem poles. Language revitalization and preservation is the most important issue of our time. We'll have to spend the rest of our lives fighting for it."

For the language project, Boxley will move from Washington back to Alaska. Ironically, he's at the same age his father was when he made a life-changing move years ago. "My dad was teaching, owned an ice cream shop, and carved," he said. "And he moved to Washington to carve full-time, which was very risky if you think about it. I'm at that same age."

It's all coming full circle, Boxley said.

"Everything I've done so far is sending me back home with a good set of skills to help my people," he said. "When you're in your 30s, you start thinking, 'What am I leaving the world?' If I can solidify that return to tradition and culture and a sense of belonging for where we live, that will be enough."