Honoring the Collective Spirit®

By Lori Pourier, President of First Peoples Fund

When Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco/Wishram) nominated Bud Lane III (Siletz) for the Community Spirit Award in 2009, she described him as a person who “honors the Creator in many ways; the medicine plants, basketry plants, the Siletz people and for all life.” Pat, herself an internationally known fiber artist, basket weaver and 2004 CSA honoree, understands the true meaning of community spirit. She understood that Bud — who was selected for the CSA and later became a member of the FPF board of directors — embodies that true meaning.

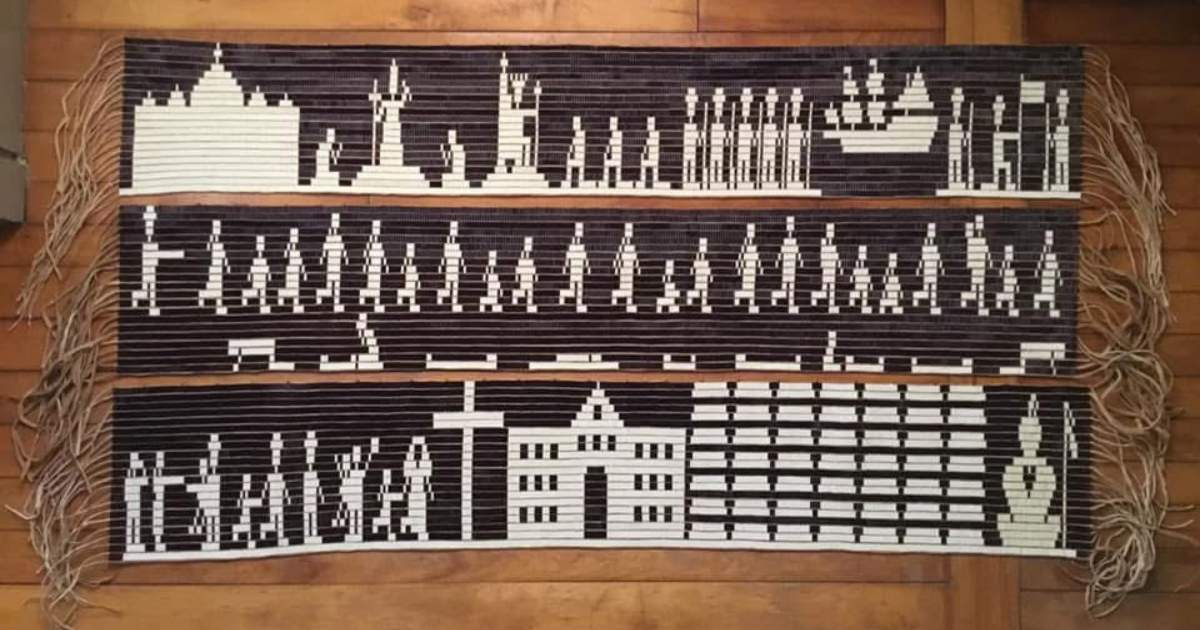

During a recent board meeting, we visited the Siletz Tribe on the Oregon coast, and First Peoples Fund staff and board members learned first-hand what drives Bud, in his role as a father, culture bearer, language teacher and tribal leader. Bud began our day by grounding us in prayer in the Siletz language. He surrounded us with a table full of beautiful baskets he had woven. In addition to spending the past 30 years restoring Siletz basketry, regalia and dances, Bud is committed to teaching Siletz language. The depth of his commitment to teaching other tribal members quickly became apparent when we learned he would be driving four hours round-trip to teach language lessons after our first full day of meeting.

Bud also shared a slideshow demonstrating the history of the Siletz tribe and 50 other tribes who by 1854 were forced to relocate along the Oregon coast and near present day Lincoln City. In that slideshow, we saw the roots of Bud’s own tenacity. We learned of the old people who fought to hold on to their ways after the signing of The Rogue River Treaty of 1862. The treaty guaranteed the tribes nearly 1 million acres of uninhabited timberland and coastal shoreline. Just 20 years later, most of the land would be taken illegally, first by executive order then by an act of Congress. The Dawes Act of 1887 would further divide remaining tribal land into individual allotments. By 1954 the Siletz tribe was terminated, meaning they lost their federal recognition, eliminating any trust responsibility held by the United States government. The Siletz tribe would not regain federal recognition until 1977 following a long struggle. The Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians was only restored 3,600 acres of their original treaty lands. Hopeful Bud said, “It’s not 1 million, but it’s a start.”

Following our board meeting, we accompanied Bud to the community center where their tribal archives hold more than 300 baskets and other ancestral items that found their way home. “To see our people making and proudly wearing ceremonial caps and work caps, carrying our children and grandchildren in our baby baskets, wearing bark capes and dresses, using traditional mats, and cooking and eating from baskets to me is preserving the very core of our collective tribal existence,” Bud said.

As Bud held each basket with pride, I reflected on Pat Courtney Gold’s words, “He honors the Creator in so many ways.”

Our day ended in the traditionally built dance house around a fire listening to Bud drum and sing the songs of the Siletz tribal ancestors. All of us left that day renewed in the collective spirit. As we parted ways Bud may not have known it but he left an unforgettable impression on each of us. And, as our family of Community Spirit honorees grows (nearly 100 this year) we are reminded of our responsibility to uphold our values and stay on our path. We at First Peoples Fund are fully committed to our three-year strategic directions: Investing in our own Collective Spirit® to adapt and grow for our future generations.